Black History, Black Present, Black Future: Exploring the Tulsa Race Massacre from an Economics Lens

By Kimberly Ellis and Vanessa Williams

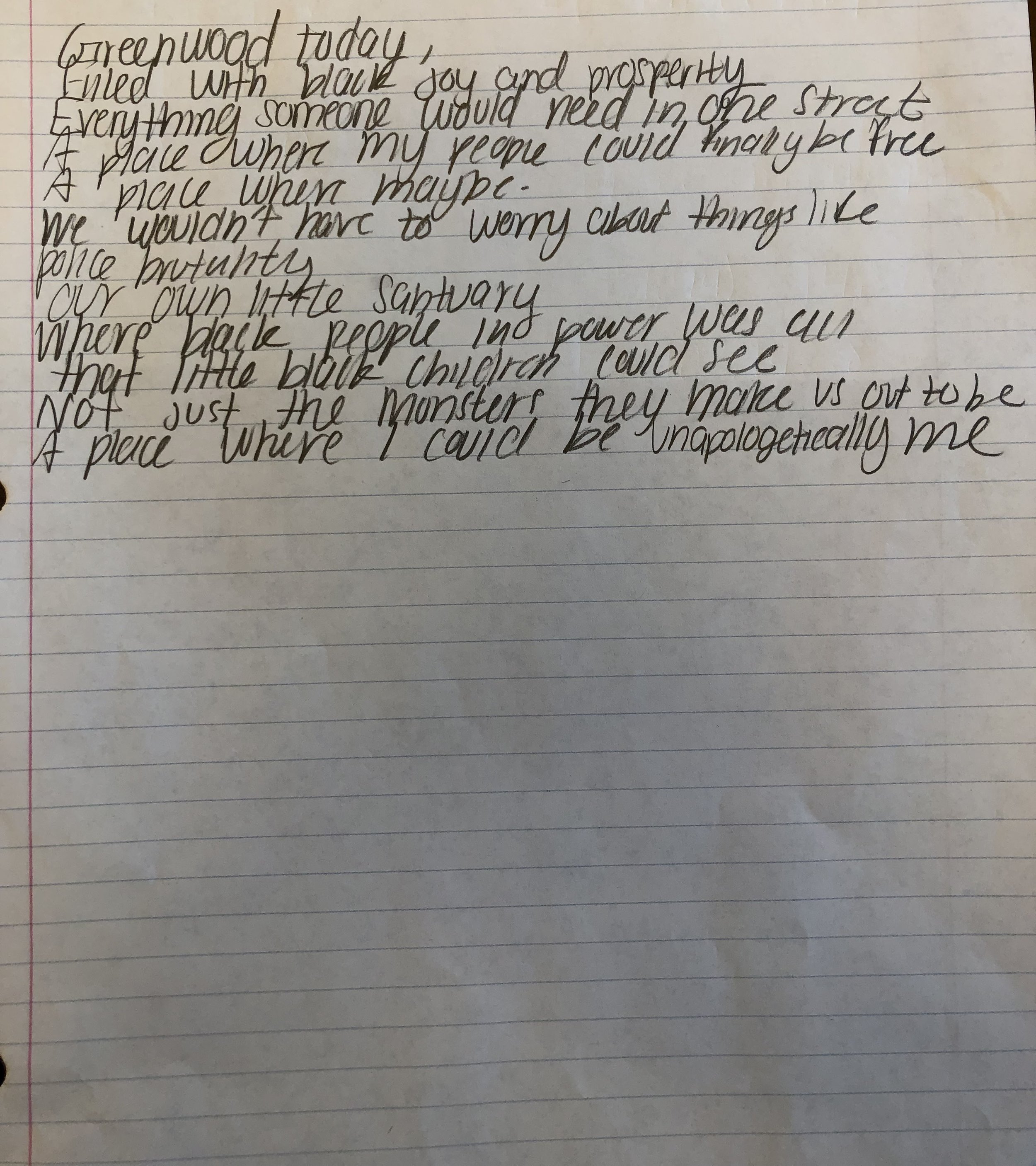

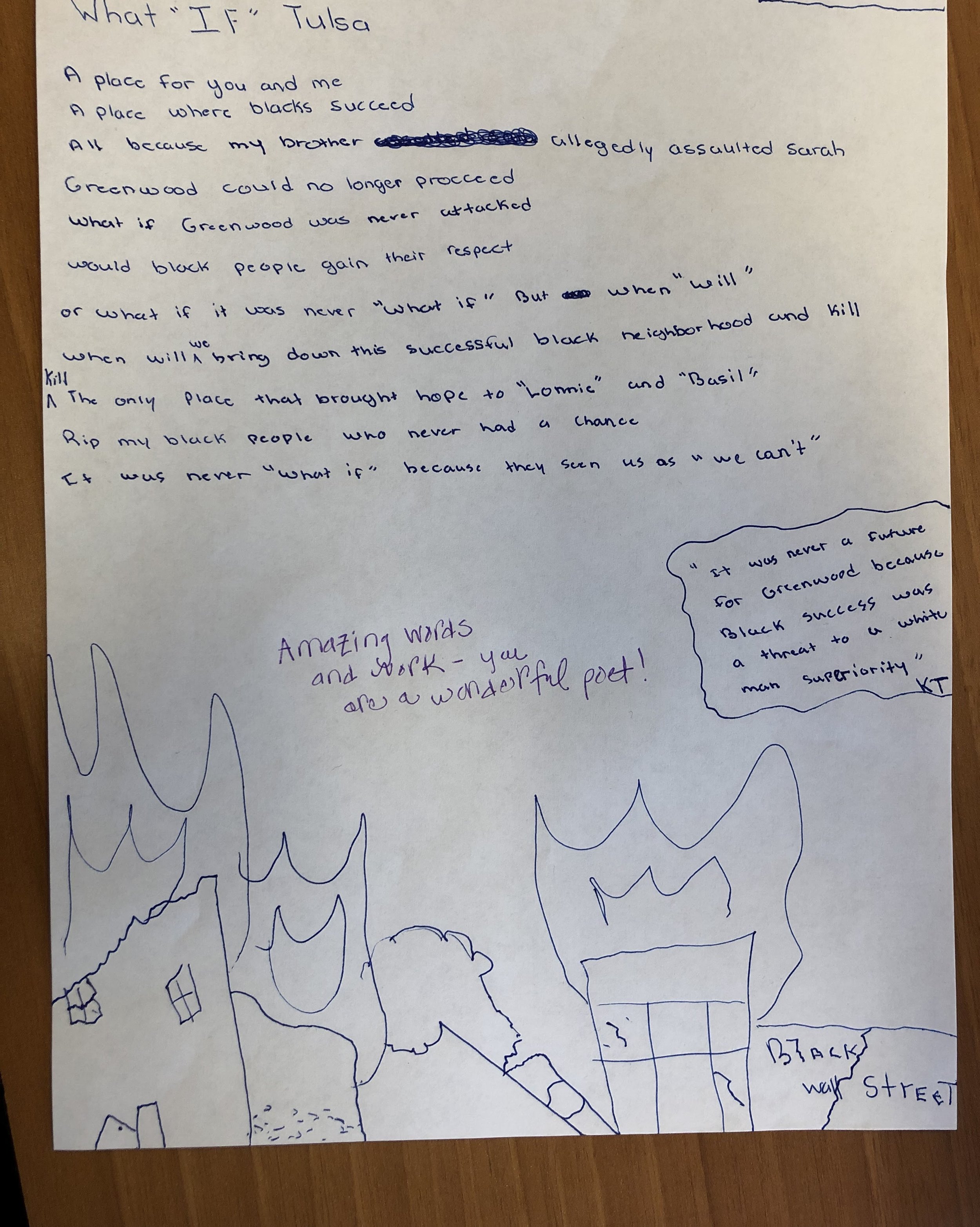

A student’s reflection on the question: “What if the Tulsa Massacre did not happen?”

What is the Tulsa Race Massacre? How do we, as a nation, tell the story of the massacre? What is owed to the Black community as a result of the massacre? Ashley Bryant created two weeks of lessons to explore these questions in celebration of the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action and Year of Purpose. Through a critical economics lens, Bryant taught about the Tulsa Race Massacre and socioeconomic impacts on the Black community. Bryant is a 2021 Teaching for Change fellow who is currently teaching 10-12th grade Economics at Academy at Palumbo (The School District of Philadelphia).

Students first learned about Greenwood by exploring accounts of business and families lost. In order to grapple with the larger questions of their exploration of the Tulsa Massacre, Bryant and her students did a close analysis of primary source documents to discuss: “What caused the Tulsa Massacre?” In the student-led Socratic circle, some offered up that the massacre started because of white rage and fear over Black wealth and prosperity, citing specifically Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s writing about lynching culture at the time. Students also highlighted the media’s impact on constructing the narrative that came out of Tulsa and how even primary source documentation can leave information about history unknown. Towards the end of the seminar, one student weighed in and brilliantly connected so many themes that Bryant sought to impart with her students:

I feel like it was not necessarily this child directly that caused it. I feel like it was more about power and how Black people were sort of showing that they were of equal footing to white people. I feel like the point that Ida B. Wells made, that lynchings are often a [threat] against Black people, to punish them. It’s always a woman, specifically a white woman, who’s at the center of it, saying that she’s been harmed in some way. And it’s happened multiple times. So I kinda feel like the moment this white woman accused this Black man of assaulting her, it was downhill from there. Before this article even came out, it talks about how the trial– or the incident happened yesterday, and the very next morning he was arrested on a state level crime, which is like, clearly he wasn’t going to get a fair trial to begin with. And then I feel like, even if this article didn’t come out, most likely he was gonna be lynched. I feel like the article only called other white people, like everybody else was saying, to sort of come and exert their power in that situation. I feel like Tulsa is a big example of what can happen if white supremacy goes unchecked. Any time Black people show that they’re on equal footing, or show any form of success, then, of course white people will come to make sure, or to remind them that they are supposed to be inferior.

Although they didn’t have time to wrestle with it, Bryant displayed a powerful quote from Carol Anderson’s White Rage for students to consider:

Trigger for white rage, inevitably, is Black advancement. It is not the mere presence of Black people that is the problem, rather, it is Blackness with ambition, with drive, with purpose, with aspirations, and with demands for full and equal citizenship.

While the time for this discussion was brief, it was impactful.

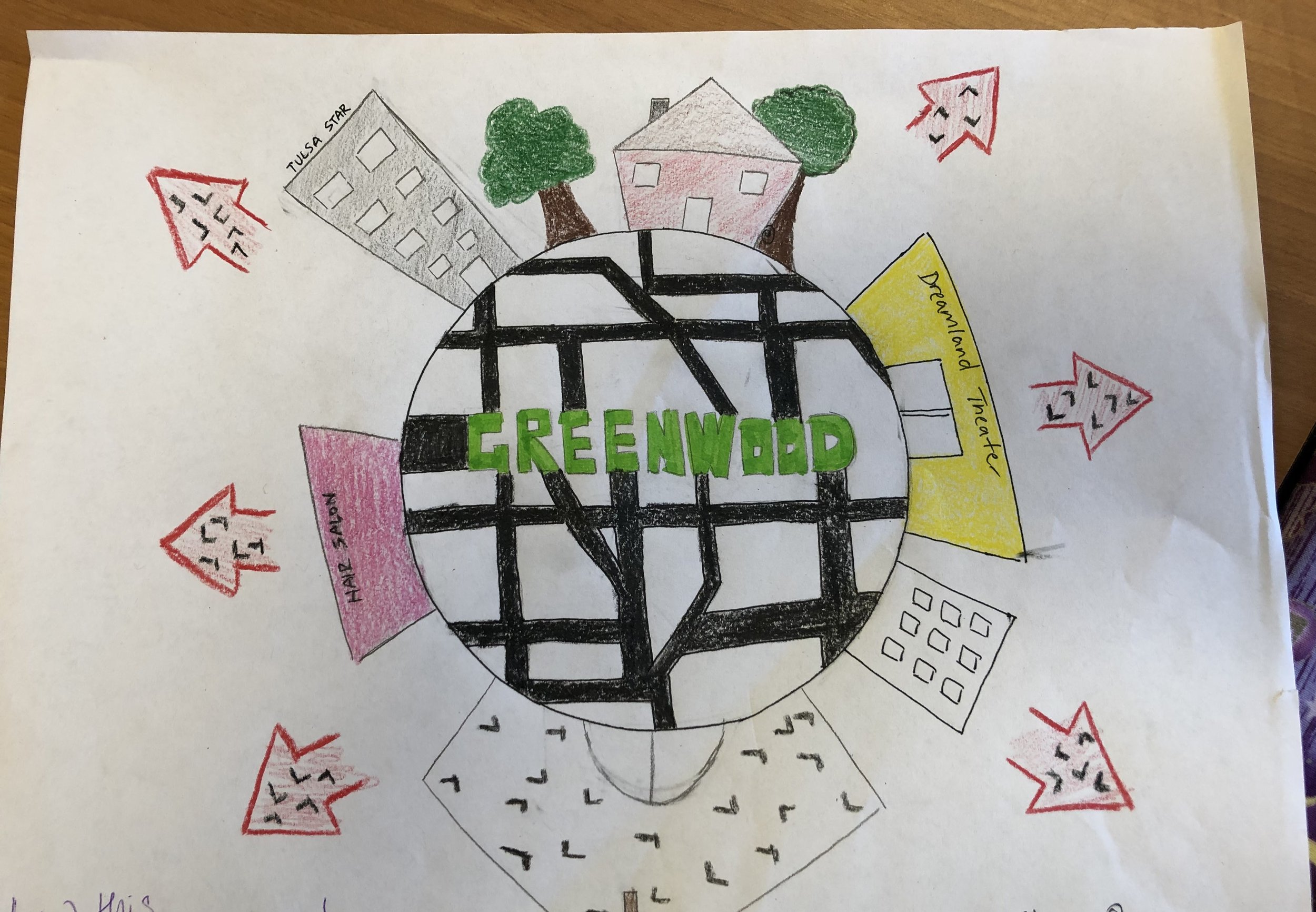

In her next lesson, Bryant focused on the loss of Black wealth caused by the Tulsa Race Massacre and the impact on future generations. Students began by processing the previous lesson through three options: choose a word to describe the massacre, engage in a free write to process the material, or use class resources (slides and article) and share one thing that resonates. After independent reflection, students watched a video documenting the memories and experiences of people whose relatives survived the Tulsa Race Massacre. Bryant then showed a map of present-day Greenwood to further contextualize some of the information presented in the video. The class compared this map to maps of the district prior. Students pointed out how the present-day map of Greenwood showed several new interstate highways. They discussed how the federal construction of these highways was used to demolish, divide, and isolate Black communities and other communities of color, noting similarities in their own city of Philadelphia with plans to build a highway through South Street.

Bryant then introduced a podcast highlighting research by Dr. Lisa Cook showing how Black invention has been historically stifled by segregation and racial violence. After listening to an excerpt of the podcast, students discussed Cook’s argument: years of racial segregation and violence, and in particular the Tulsa Race Massacre and the lack of government support for victims, contributed to a sharp nationwide decline in patent filings by Black inventors. Subsequently, not only have generations of Black Americans lost wealth, but also the entire country. Students identified other examples of racial violence around the time period of the Tulsa Race Massacre, such as Red Summer in 1919.

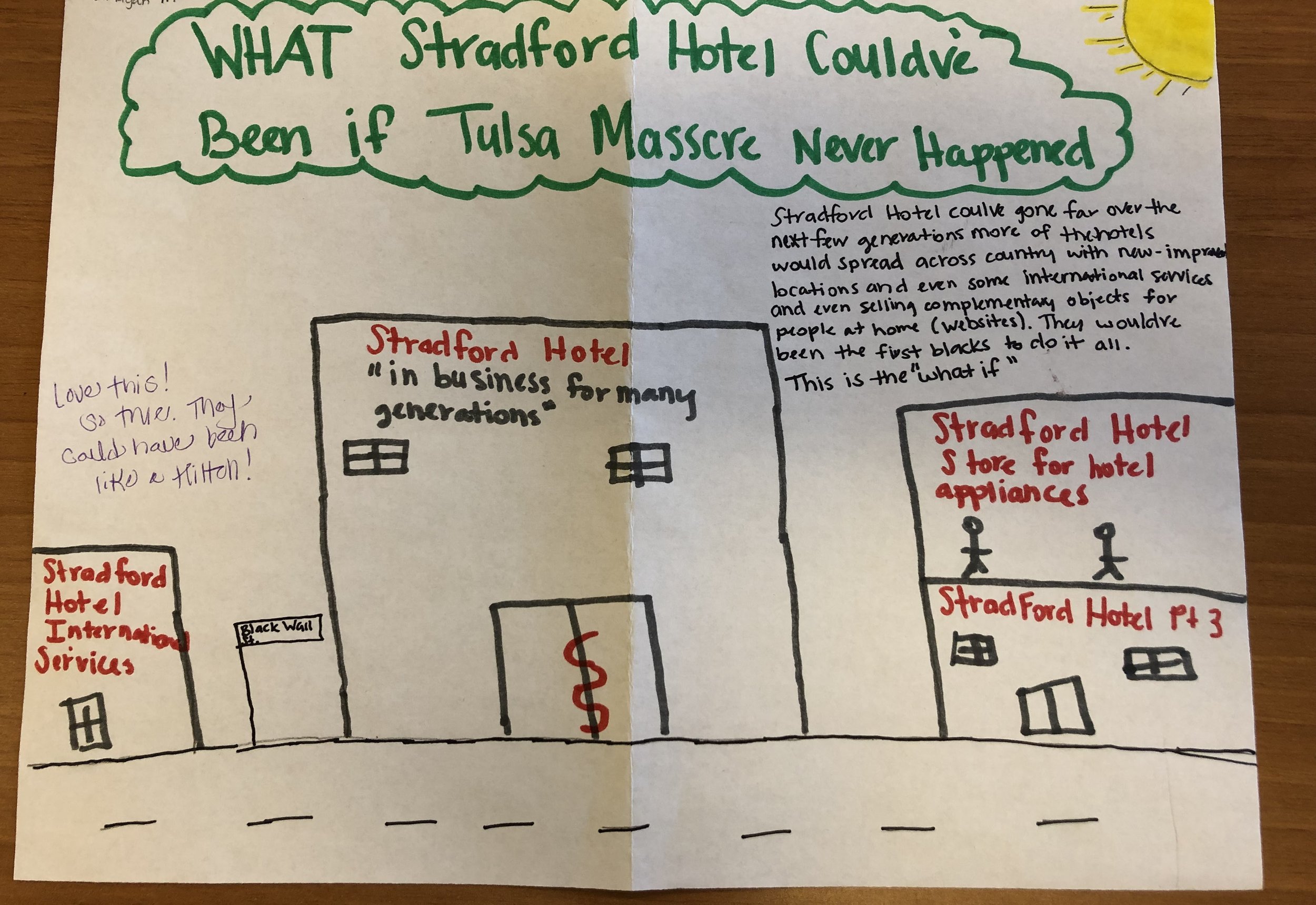

As the culminating activity, students imagined what Greenwood, and the Black community in Tulsa, could have been. Bryant posed three questions for reflection:

What if Black businesses were supported?

What if the Tulsa Race Massacre did not happen?

What do you think would have been possible if Greenwood were allowed to prosper?

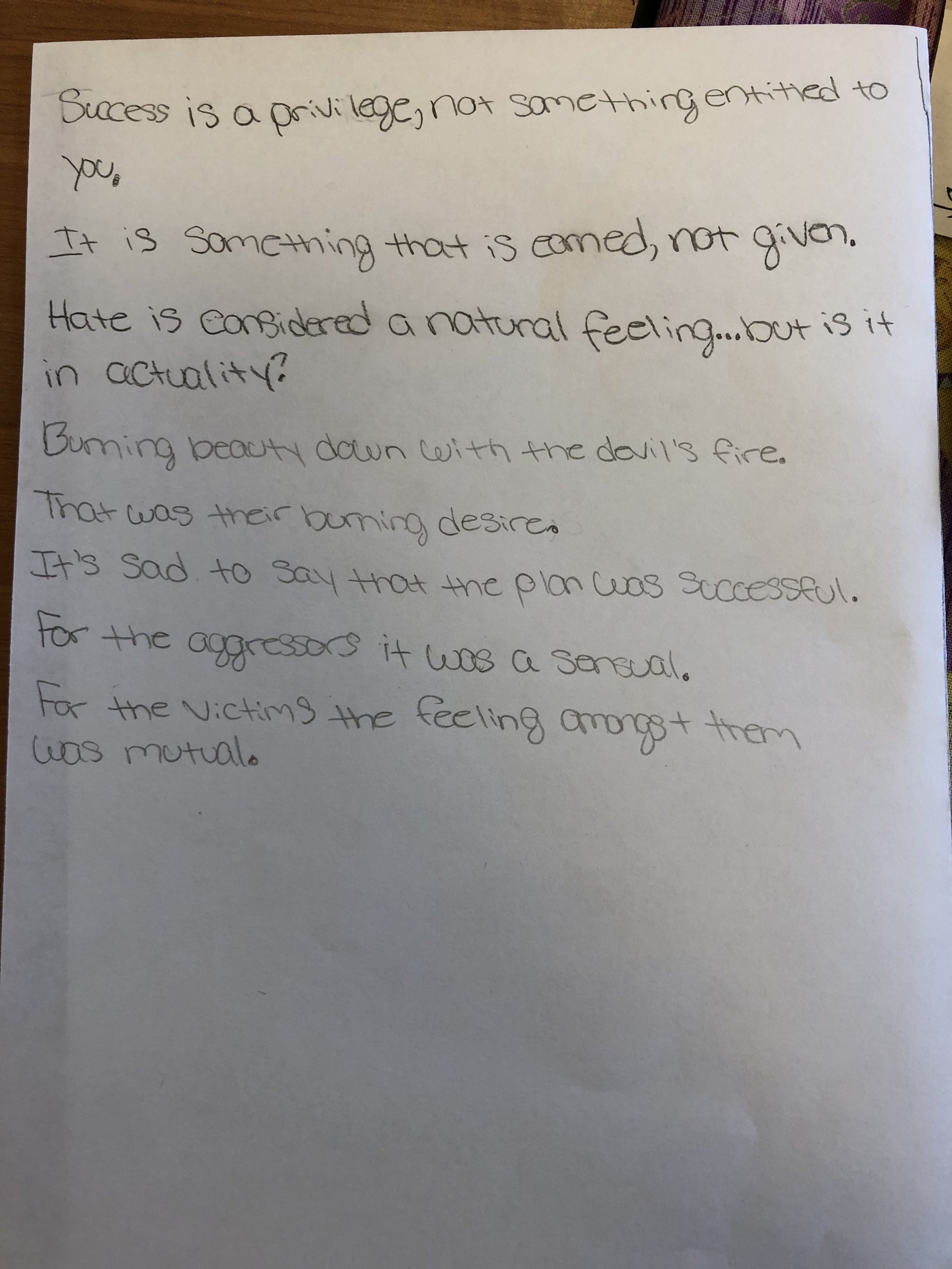

Through drawings, poems, short stories, and more, students grappled with these “what if” questions. Review some students’ reflections on Tulsa below.

In remaining lessons, Bryant’s students studied reparations, researching what is happening now to get justice in Tulsa, as well as examining accounts of other tragedies and how reparations were approached. Many students noted how Tulsa needs to be taught in schools around the country. Reflecting on Chicago’s commitment to teach the history of police torture in eighth and tenth grade social studies classes, students described education as a powerful form of reparations to tell the truth of what happened so it does not happen again. Students then explored reparations from an economics lens, breaking it down to determine a feasible economic plan. Black history, Black present, Black future — Bryant and her class explored them all in their deep dive into the Tulsa Massacre reifying the purpose of Black Lives Matter at School.

Find more resources to teach about the Tulsa Massacre, including a lesson, children's and young adult books, an online graphic booklet, an online map, and more.

Vanessa Williams is a Program Manager for D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice.

Kimberly Ellis is an Education Anew Fellow with Teaching for Change and Communities for Just Schools Fund. Read more of her stories.